Art reviews: Decades: The Art of Change, 1900-1980 | William Gillies | Peter Howson

Decades: The Art of Change, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh ****

William Gillies: The Visionary Painter, Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Advertisement

Hide AdPeter Howson: A Retrospective, City Art Centre, Edinburgh ****

Split between two venues, Modern One and Modern Two, the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art has a constant problem: how to display its collection coherently when the collection itself is not really strong enough to be split? A while ago Modern One was rehung with the title Conversations with the Collection. The idea was to find associations between works across the generations. The result is really a bit of a jumble, nor is it helped currently by the extravagance, whatever her merits, of the whole ground floor being devoted to an exhibition of the work of a single artist, Alberta Whittle. Meanwhile, Modern Two has been rehung with Decades: The Art of Change, 1900-1980, a display whose title plainly reinstates chronology as indispensable. Ideas grow and change and they do so over time, but also space. Geography matters too. National schools are not just vanity. The Scottish presence in the new hang is uneven, but then so is the SNGMA’s Scottish collection.

The gallery’s remit has always been art since about 1900. The modern as it was more than a century ago was seen as somehow different from anything that went before. It is a rather shaky idea, but when you look at Matisse’s La Séance de peinture, a key work in the collection hanging here in the first room, the informality that gives the picture such effortless grace does perhaps set it apart from older traditions. Here it hangs mostly with other casually executed pictures more or less within the first two decades of the 20th century, the blazing colour of Derain’s wonderful Collioure from 1905, for instance, or Robert Delaunay’s Equipe de Cardiff with the Eiffel Tower and a box-kite aeroplane as quaint symbols of the modern. In the same gallery are works by the Colourists, Peploe, Cadell and Fergusson, which do look good in this company, especially Peploe’s little blue and white picture of Paris Plage. There is Picasso’s beautiful Mother and Child from 1902, but no proper Cubist painting which would have helped make sense of the next room, devoted to essays in abstraction in the 1930s. Mondrian hangs at the centre, but the rest are British artists. Striking essays in abstraction by Ben Nicholson and Margaret Mellis reflect the impact of Mondrian’s brief stay in London. A big and untypical work by John Piper and other essays in more associative abstraction reflect the impact of Surrealism after the major exhibition in London in 1936.

There is no William Johnstone here, though he was a pioneer of surrealist-inspired abstraction, and his protegés Eduardo Paolozzi, Alan Davie and William Turnbull all feature in the first two rooms upstairs. Titled “The 1940s: the Horrors of War” and “The 1950s: Anxiety and Reconstruction”, these take us through the years of post-war angst. In the first room, Benno Schotz’s very fine grieving figure, The Lament, from 1943 is beautifully apposite. A still life by Robert MacBryde and a very similar still-life by Picasso clearly reveal the dependence of one on the other and indeed Picasso’s influence was pervasive, but three of Paolozzi’s terrific bronzes from the late 1950s standing together show how even his influence could be fruitfully absorbed.

These bronzes preside here, but there are also other very striking things. Hanging together, for instance, Bet Lowe’s portrait of a Man Smoking from 1945 and Joan Eardley’s Street Kids and her Sleeping Nude make a powerful statement. (A male nude painted by a female artist created a scandal, as though the opposite had not been happening for centuries.) It is also fascinating to learn that Robert Colquhoun’s fierce Figures in a Farmyard with its glowering, monstrous pig straight out of Animal Farm, was actually painted for a competition to mark the Coronation in 1953.

The last two rooms follow through minimalism, performance, Op-art and a bit of Pop. Jospeh Beuys’s felt suit looks a bit lonely while Fred Sandback’s Untitled 1971, a piece of coloured wire stretched across the corner of the room, is really so minimal it scarcely has any presence at all.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe same cannot the said of Duane Hanson’s wonderfully observed tourists, and it is good to see the too long neglected artist Carole Gibbons given space with a fine painting called Elegy. There is a very good Alan Davie, a couple of Bridget Rileys and of course the SNGMA’s ever popular Lichtenstein, In the Car. It’s really a bit too much to try to pack the last 50 years or so into just two rooms, but given its space restraints the gallery has to try.

In the second room downstairs, along with the abstract work of the 1930s, are works in a very different almost faux-naive, figurative mode by Christopher Wood, Ben and Winifred Nicholson. This was one starting point at least for William Gillies. In the 1930s he experimented more adventurously, but an extensive show at the Scottish Gallery, William Gillies: The Visionary Painter suggests that in landscapes at least he stayed within quite a narrow range of apparently swift and spontaneous responses in which the sophistication of what he was doing was always well concealed. The show includes 50 works. The great majority are watercolours, or indeed drawings, and they range from the ’30s through to shortly before his death in 1973. A lovely picture, Near Laide, Wester Ross from 1937 clearly shows an affinity with the assumed naivety of Ben Nicholson’s Walton Wood Cottage of 1928. Gillies’s naivety may equally be assumed, but he nevertheless somehow managed to keep a kind of innocence. It is there in Hill Croft from 20 years later, for instance, and it is what gives his work such enduring appeal. His drawing can be quite precise, as in a lovely painting of the church at Cartmel in Cumbria, made in a rare foray south of the border, but even so the picture keeps the freshness which is hallmark Gillies.

Advertisement

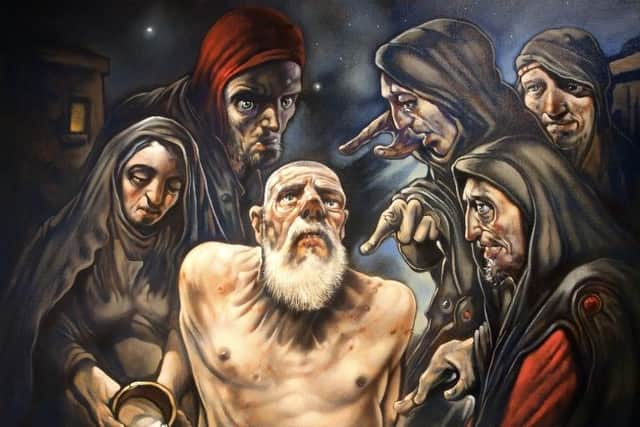

Hide AdFreshness is not the hallmark of Peter Howson, however. Nor is economy. Indeed, the work from more recent years in his retrospective at the City Art Centre gets quite overwhelming. Throughout the show there is a constant preoccupation with a kind of brutal masculinity. Indeed, apart from a single nude Madonna there is hardly a woman anywhere unless she is being subjected to violence, as in a harrowing series of paintings that Howson did of the Bosnian war.

Howson was brought up in Glasgow and trained at Glasgow School of Art and in earlier pictures like The Wages of Sin from 1991 there are echoes of Steven Campbell, leader of a figurative revival in the early 1980s when Howson was a student. But Campbell was a subtle and immensely varied artist. Howson, in contrast, soon settled into the repetitive, brutal, macho imagery which is now so familiar and which is seen already, for instance, in Blind leading the Blind (Orange Parade), also from 1991. Often he is at his best on a small scale, as in the Saracen’s Head prints, a set of etched portraits of individuals from a Glasgow pub, or in very powerful expressionist drawings of individual heads in Bosnia. In these, heavily over-muscled flesh gives way to something more abstract and the effect is actually more visceral.

Much of Howson’s dark vision is apparently rooted in his experience and this includes religion. If so, his wild paintings suggest that for him religion is a ferocious and terrifying experience. That was also certainly true for John Bellany, but for Bellany there was at least the occasional epiphany if not redemption. There is not much sign of redemption here. Howson’s world is unrelievedly dark.

Decades: The Art of Change, 1900-1980, no end date; William Gillies until 24 June; Peter Howson until 1 October